Links #3: Favorite Reads from Last Week

AI to engineer biology, the crimes behind our seafood, elder statesman Tony Bourdain, and the forever chemicals coursing through our blood

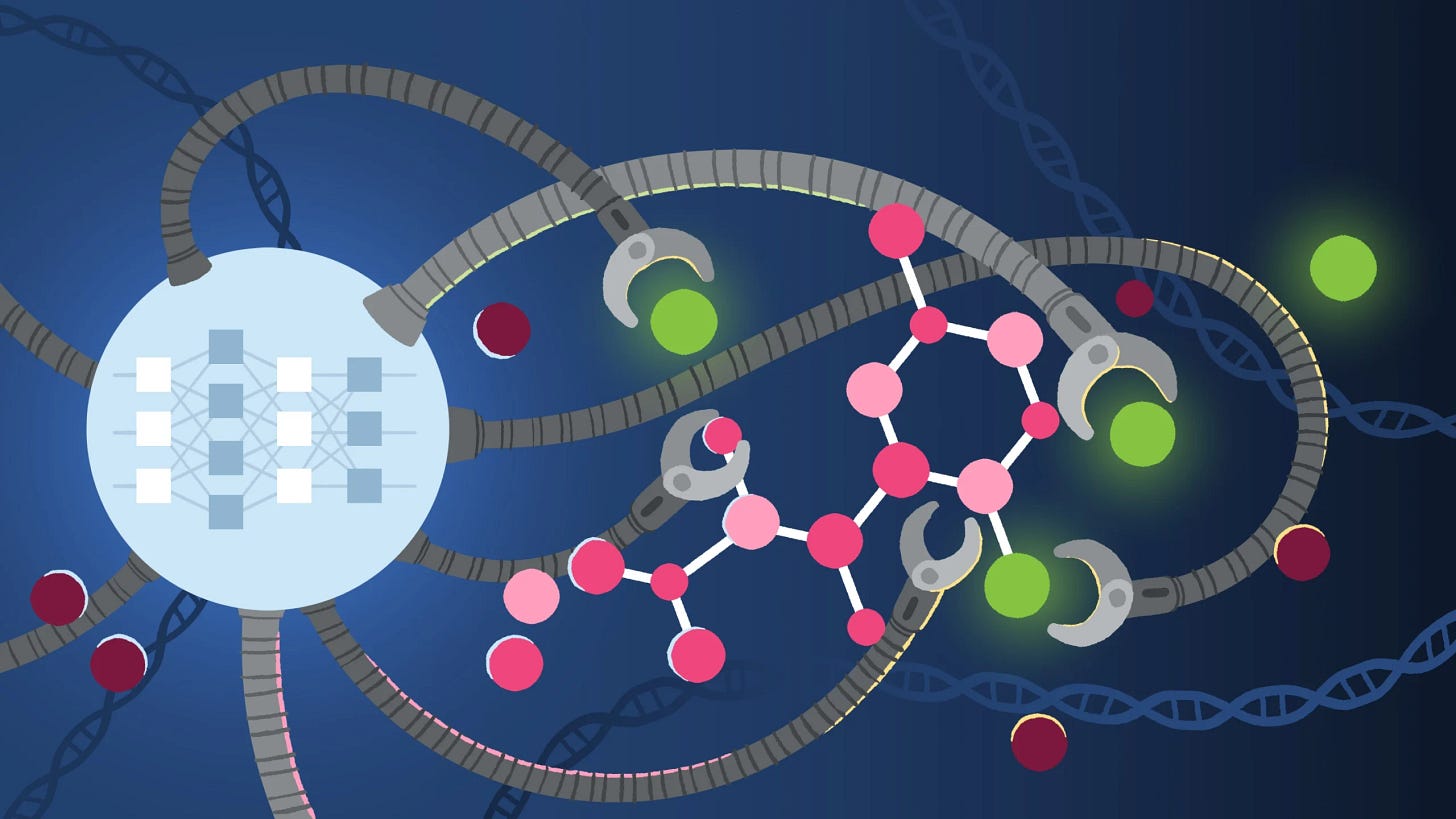

1. ESM3: Simulating 500 million years of evolution with a language model

by EvolutionaryScale Team

EvolutionaryScale came out of stealth to announce a new LLM for biology, with the aim to use “AI to engineer biology from first principles.” They also announced that they’ve managed to use this model to create (or is it discover?) a new green fluorescent protein (GFP) — the kinds that allow jellyfish and corals to glow — which they’ve named esmGFP. The AI-generated protein is “only 58% similar to the closest known fluorescent protein”, a change they claim is estimated to be “equivalent to simulating over 500 million years of evolution.”

That’s… a lot to process. I’m not an expert on LLMs, but I do know the basics of how it functions, so there were some interesting aspects they mention, along with some questions (I assume some will be explained in more detail in the preview paper, which I’ve not read yet):

they’ve transformed the three fundamental properties of biology — sequence, structure, and function — into a new token data format (set of discrete alphabets) so that the model can be trained on all simultaneously and promise “unlocking emergent generative capability.” I’m curious about this data transformation; I think it’s important that the connection between these three properties are promoted in training, versus just depending on a single data point, like sequence, for example.

they’ve augmented the training dataset with “hundreds of millions of synthetic data points” because they have limited amounts of annotated experimental data. I wonder if the limitation is experimental data, or experimental data annotations here. If it’s just annotations, how can more experimental data be annotated at scale? Or is it not required as much because synthetic data is quite a capable substitute? And how is the validity of synthetic data tested prior to training?

ESM3 is self-improving, but they also mention that “feedback from laboratory experiments or existing experimental data could also be applied to align ESM3’s generations with biological success.” How would this be done in practice, taking into account the data transformations? What does fine-tuning with this model look like?

they also mentioned that ESM3 generated protein candidates with a chain-of-thought process, after being “prompted with the structure of a few residues in the core of natural GFP.” Can this chain-of-thought be visualized? If the claim is “equivalent to simulating 500 million years of evolution”, looking at how the model got to where it ended up on — and what the intermediaries looked like — could be interesting, and also maybe provide insight into the models “evolutionary path” for the engineered GFP.

I am, however, a bit skeptical about the responsible development and public benefit company status. I think that things can change, and a single lucrative discovery might lead to changes in company structure or slight changes in the accepted community values, guiding principles, and commitments, like with OpenAI. That being said, I’m excited to read what scientists and researchers have managed to do with the model so far, and what they’ll use if for in the future, as well as to learn more about AI and biology.

2. The Crimes Behind the Seafood You Eat

by Ian Urbina

This is a difficult read, but an important one. Urbina’s reporting is stellar, following sources and leads for years, and going to extreme lengths to give a voice to the unheard. (One I particularly admire was how his team, when denied access to come onboard a vessel, followed it in a skiff and threw bottles filled with a paper with questions and rice for weight on-board, which were then answered, put back in the bottle, and thrown back to them).

The story of Aritonang is tragic, and to think that he’s just one of tens of thousands — millions if you take into account other industries — of people trapped in modern slavery. Life on a distant-water fishing ship is arduous in the best of conditions, so it’s impossible to grasp how terrible and hopeless life must feel when servitude is tacked on top.

It’s difficult to conceive of a near-term solution to any of this. Like Urbina explains, distant-water fishing fleets are extremely difficult to track, and ensuring vessels meet international maritime standards is nearly impossible to ascertain, especially when accounting for geopolitical alliances. Import bans are difficult to uphold because seafood from the illegal vessels can be secretly transferred to other vessels, essentially white-washing it. After it reaches a processing facility near the port, it again gets harder to separate the legal from the illegal, and so, likely a significant portion of important seafood — particularly squid, that this report details — comes from illegal vessels.

In between processing sorrow for Aritonang and others like him, my mind kept considering one possible long-term solution to both this crime and the problem of overfishing: lab-grown meat. I remember, while I was doing my Terra.do class last year, we had discussed lab-grown meat as a future alternative for meeting worldwide demand while still reducing meat’s climate footprint (land for cattle, overfishing, etc.). Companies like Wildtype Foods, for example, already grow salmon from cell culture in their microbrewery-like lab, and as of October 2021, produced 50,000 lbs of it per year this way. I’d guess there’s no reason squid can’t be made the same way, or beef or chicken. The question is: can it scale? And, if so, can the public be convinced it’s the same?

3. Anthony Bourdain’s Moveable Feast

by Patrick Radden Keefe

I’m a huge Anthony Bourdain fan. I, like millions around the world, watched Parts Unknown and No Reservations with deep interest, intrigued by this brash-yet-likeable man’s incredible ability to combine discovering and devouring mouth-watering local cuisine with the region’s cultural and political discourse. I read Kitchen Confidential almost two years ago, and marvelled at both his wild upbringing and the cocksure, gruelling kitchen environment, written in much the same vigor and punchiness.

I’m also a huge fan of Patrick Radden Keefe. I first came across his writing through his book, Say Nothing, the shocking and violent account of the Troubles and its impact on Northern Ireland. I read it three-and-a-half years ago, and I can still picture some of its haunting imagery of countryside murders and terrorist bombings. I naturally kept track of Keefe’s writing since, so when Empire of Pain launched I immediately added it to my list. I finished it last month, and again, I was in awe at Keefe’s ability to report, so clearly and deftly, on a topic that for decades had been purposely twisted and concealed in a shadow of deceit and mystery.

As I looked through Keefe’s older New Yorker articles, I was surprised to find that he had published a short essay on Anthony Bourdain the day after Bourdain died, which mentioned a profile (this one) he had written a couple of years earlier. It felt like two of my worlds colliding. I had no idea that Keefe, traveling with Bourdain for the profile, met up with him in a Hanoi bar the day after that famous dinner with Obama at the bún chả restaurant was filmed. Reading this felt like witnessing behind-the-scenes footage from that popular segment, filmed by a character I had assumed distinct from the world of Bourdain. (I had, in fact, visited (but didn’t eat at) that same restaurant early last year when I went to Hanoi, vaguely following the trail made by his show.)

Crossover-episode-style fun aside, this article is another literary gift from Keefe. He, as I also felt in Say Nothing and Empire of Pain, seems to be a master in probably what is the most important skill as a writer: getting the reader to read the next sentence. Maybe partly it’s the thrilling subjects he writes about — violence and murder in Northern Ireland, nationwide pharmacological white-collar crime — but nonetheless I find myself gliding through the text, completely engaged, almost incapable of giving up attention in my otherwise occasionally-distracted mode of reading. Even if you’re somehow not a watcher of Bourdain or a reader of Keefe, this is a pretty good place to start.

4. How 3M Executives Convinced a Scientist the Forever Chemicals She Found in Human Blood Were Safe

by Sharon Lerner

This was another frustrating read about scientists and executives actively concealing important information from the public, and then, once the crimes comes to light, getting away completely unscathed. After last week’s carcinogens article, this one sheds light on a new threat: forever chemicals. Despite 3M knowing, since the 70s, that their fluorochemicals were seemingly everywhere and in everyone, they hid that information from employees, state and federal authorities, and the general public, until they were forced their hand. Lerner follows the story of Kris Hansen, and her conflicted role not in hiding, but rather ignoring what she knew to be a very serious problem.

This article also serves a great example of why having a company police itself for environmental and public health matters is unlikely to work; the incentives are just not there for executives to publicize their mistakes early, when the damage is still containable. Instead, you end up with this tragicomic if-I-didn’t-look-it-didn’t-happen story, where each person in the hierarchy wonders why no one is believing and following up on this very serious issue and eventually ignores it. Years or decades later, when the people in the story look back at their actions, the best you can get is a feeling of remorse, like with Hansen, and at worst malice, like with her boss, Johnson.

Another pattern I keep finding is of companies settling lawsuits with the inclusion that they don’t admit fault or liability. 3M paid $850 million with this condition to settle the lawsuit brought by the Minnesota attorney general. It was also the modus operandi of Purdue Pharmaceuticals and the Sackler family, as described in The Empire of Pain. The fine, generally, is inconsequential to the company’s bottom line; simply the cost of doing business. But the long-term damage to public health and state budgets, both in the case of Purdue and 3M, are astronomical. I wonder if it’s just going to continue this way. What changes in legislation would be required to make safety checks proactive to potential dangers, rather than reactive to damage done?